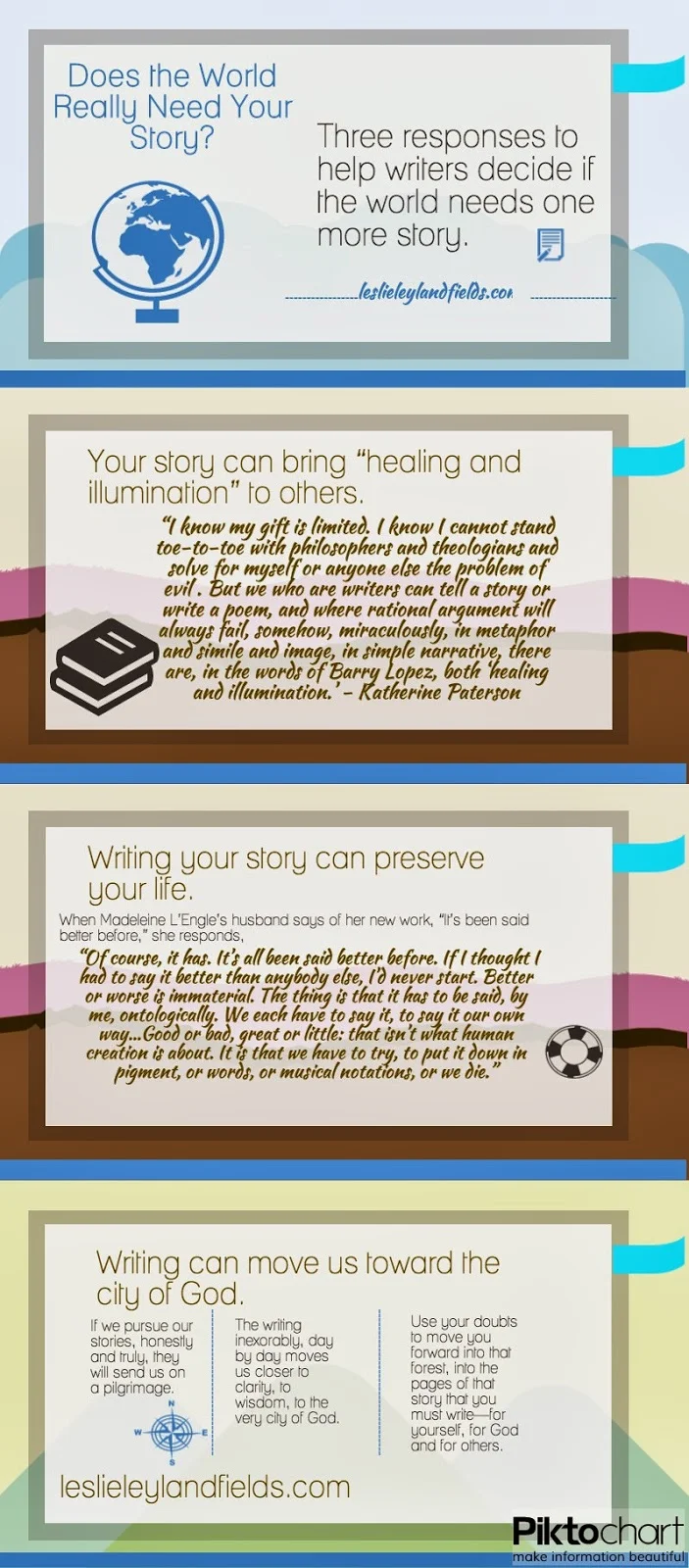

Does the World Really Need Your Story?

This week snow fell–again, about a foot, on top of already knee-deep layers. I strapped on skis and went off into a spruce forest near my house, my tracks the first marks on the page of the world.

Starting a new writing project, a book or an article, even a blog post, feels much like this. I see something falling outside my window–an idea, a passion, a glimpse of something true and maybe beautiful. I eagerly strap on metaphorical skis and go out, wondrously lost in a world made strange again. I am confident that I belong here, that I will apprehend something of value and meaning. But the going gets hard. The surface of the snow changes. The skis get stuck. I fall. I discover dozens of tracks before me on the trail, most more graceful than my own. Why am I here?

Doubts track me down no matter where I am. I have learned not to dismiss them. They force me to consider and reconsider. Does the world really need one more story?

Today, I give three responses: two from others, one my own.

1. Your story can bring “healing and illumination” to others.

Katherine Paterson, prolific Newbery award-winning author, says with genuine humility, “I know my gift is limited. I know I cannot stand toe-to-toe with philosophers and theologians and solve for myself or anyone else the problem of evil . . .” But here’s what we can do, she says, “we who are writers can tell a story or write a poem, and where rational argument will always fail, somehow, miraculously, in metaphor and simile and image, in simple narrative, there are, in the words of Barry Lopez, both ‘healing and illumination.’ Here I see a word of hope and possibility.”

2. Writing your story can preserve your life.

When Madeleine L’Engle’s husband says of her new work, “It’s been said better before,” she responds, “Of course, it has. It’s all been said better before. If I thought I had to say it better than anybody else, I’d never start. Better or worse is immaterial. The thing is that it has to be said, by me, ontologically. We each have to say it, to say it our own way. Not of our own will, but as it comes out through us. Good or bad, great or little: that isn’t what human creation is about. It is that we have to try, to put it down in pigment, or words, or musical notations, or we die.”

3. Writing can move us toward the city of God.

If we pursue our stories, honestly and truly, they will send us on a pilgrimage that takes us, like Abraham, from one land to another, from a land of unknowing and darkness, through, of course, wastelands, where the promise of a promised land appears invisible and impossible . . . but the writing inexorably, day by day moves us closer to clarity, to wisdom, to the very city of God, if we allow it.

Don’t waste your doubts. Use them to move you forward into that forest, into the pages of that story that you must write—for yourself, for God and for others.