UNDAUNTED! Respite for the Weary Wounded

Sometimes the load is too heavy to bear. The load of hurt, the load of not being loved by the ones who are supposed to love us. My heart is heavy this week seeing so many divisions in our nation, and so many struggling in broken families. I know this struggle deep in my joints and bones. Would you like to lay that backpack of concrete down, finally? Here is when I began:

Three weeks after my father had a stroke, I flew down from Kodiak to be with him, just the two of us. He was in a rehab facility by then. I flew into Orlando, rented a car, and drove to the facility, wondering who I would find, what would be left. The last time I saw him, a few months before, he had all his faculties. He walked painfully slow with a walker, but he was upright and cogent, though he never said much. He barely spoke to me my entire life, or to any of my siblings. I knew something was wrong with him, though I had not yet found the name for his detachment, his inability to love others, even his own children.

This time, I inched down the hallway as I approached his room. I peered around the doorway and saw it was a room for two. A figure lay curled on the bed, and then, through a half-open curtain, I saw another man in a wheelchair. I entered tremulously.

My father was lying on his side, curled knees to chest. He was wearing shorts. His jaw hung open, all his teeth gone now. He was much thinner, yet his legs were solid still, muscular. What do I do? What do I know about this—visiting the sick, the elderly, a father? I felt as if I was supposed to know, but I didn’t. Do I wait? I had come five thousand miles, and my time was short. I didn’t want to wait. I inched closer to the bed, deciding . . . yes, I would wake him, if possible.

I touched his shoulder through the thin jersey, lightly, and watched his face. I held my fingers there for a moment, and he blinked; then eyes opened. He looked directly at me without moving his head. Seeing me, his eyes filled with tears and, still looking, he began to weep, a silent, shaking weeping, his whole body shuddering as he sobbed, his head still lying on his hands. I froze. I had never seen my father weep—or even teary or sad. He seldom showed emotions. I was torn in half. My face crumpled. I kept my hand on his shoulder to comfort his racking body, and there we were, bodies touching, both shaking in silent sobs, our faces lost in sadness and grief. I knew he could not speak or name the sorrows that shook him, but it seemed to me we wept, the two of us, for his life, for his long, sad life, for his breaking body, his tangled mind, and a tongue that was now nearly stilled. I cried that I had not seen him sooner. I cried for thirty years of absence from his life. We were crying for all that was lost to us both.

Later, I could not but wonder at this: the stroke had rendered him more fully human than I had ever seen him. I had not expected this: I saw my father through eyes of mercy and kindness. And I was sad as well.

Did it really take a stroke to render him worthy of pathos?

________________________________

Look across now at whatever terrain separates you from your father, your mother, your mother-in-law, your stepfather, even your grandparent. Is it possible that someone is there on the other side of the road, someone like you, stripped, knocked out, unable even to ask for help? Might that person be the wounded also?

I am not insisting as you look that you feel a flood of emotion, as I did in those moments. I am not even insisting on warm feelings. Instead I am inviting perspective.

As you look into your parents’ lives, consider the words of Jesus on the cross as He struggled for breath, His body so bloodied He was unrecognizable. He had done no evil, no wrong at all, ever. Yet He was executed as a criminal. Jesus hung there, pinioned like a dove, and uttered the most startling words ever: “Father, forgive them, for they don’t know what they are doing.”

You may not be able to pray that prayer right now, but consider where it leads us. It schools our hearts in empathy and “trains our spirits in compassion,” as Eugene Peterson has written. More than this, he continues, it allows “for the possibility that ‘they know not what they do.’”8 How many of our parents intended the harm they caused? How many acted in ignorance and are ignorant still? How many are stuck in their woundedness, unable to see, to move?

This is what we’re doing now. We are training our spirits in compassion. When we do this, we discover or remember again the frailty of our parents, the burdens they bore, the weight of their own parents’ sins upon them. And we’ll find something much larger happening. When we truly see others in all their humanness, we become more alive, more awake, more fully human ourselves.

*********************************************

(Excerpted from Forgiving Our Fathers and Mothers: Finding Freedom from Hate and Hurt

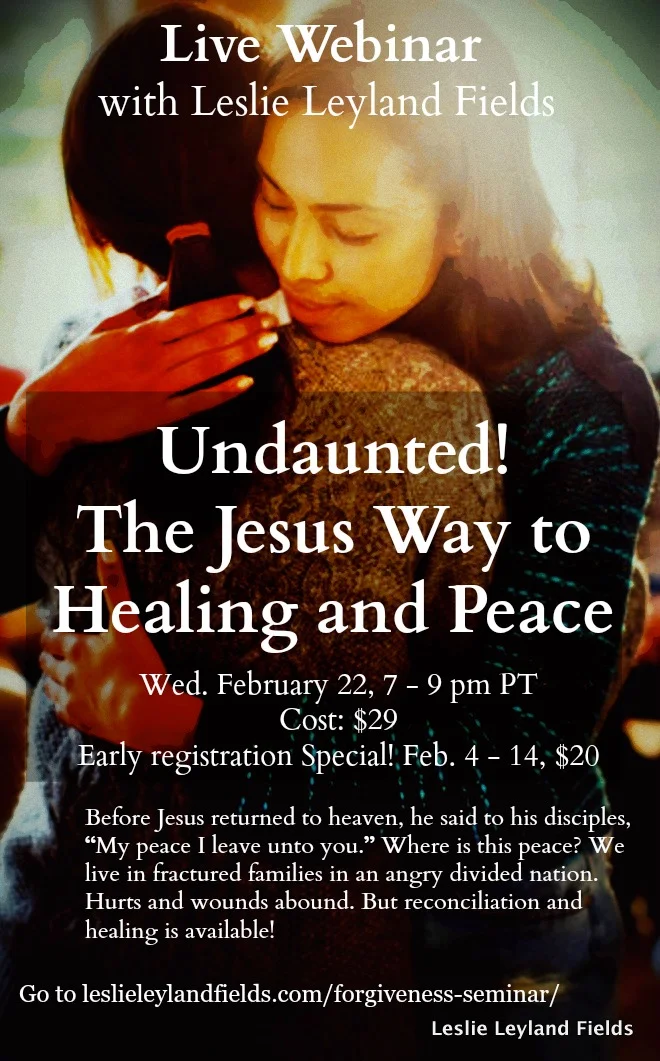

There is so much more we can do. Even in just 2 hours. The Lord has moved me to offer this Live Webinar Feb. 22. I'm offering it as affordably as I can---$20 for early registration---so all can attend. (This is the material I have used in my own life, and in prisons, workshops and churches around the country, with much fruitfulness.)

Would you join us, and lay down that impossible weight of hurt, anger and unworthiness?