Eating Worms and Going Blind in Kodiak

“It is not miserable to be blind; it is miserable to be incapable of enduring blindness.” -John Milton

Another newsworthy event—the sun shone for a good part of three days this week. To celebrate, I hiked up a snowy mountain in an icy, breath-charging wind, loving every step. The sun was so blinding I squinted through my sunglasses, agape at the colors of this winter world, too often cloaked in gray, rain and squall.

We had all been feeling the layered weight of five months of winter---knowing at least two more remains. By some measures, three. A friend writes on facebook, “I’m so tired of the dark and cold!”

My favorite winter story is about one of my sons, Isaac, who was then 2 ½. We were at the airport, taking my husband to his flight. We got out of the car, I lifted Isaac up to my hip to walk through the slush to the terminal. He kept looking upward, fussing, pointing and covering his eyes. Finally I said, “Isaac, what’s wrong?”

“Wh—wh—what is that yellow thing up in the sky?” he asked, distressed, eyes batting.

I stopped, stunned. Then, “That’s the sun, Isaac. The sun. It won’t hurt you,” I sighed as I tilted my face to its wan glow.

The weather and the dark can blind us. And it often does. But so can the sun. John Milton slowly went blind, beginning to lose his sight in his early thirties. By the time he wrote Paradise Lost, one of the most magisterial works in the English language, he was completely blind.

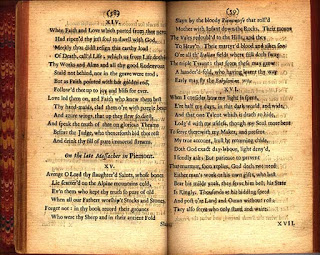

In his “Sonnet on his Blindness,” Milton laments the tension he lives within: God has given him “that one talent, which is death to hide”---his extraordinary facility with language and poetry. And God has brought as well the loss of his sight. He asks a question that has rung through the centuries, “Does God exact day-labour, light denied?” (How can God expect me to labor for Him, when he takes away what is needed to perform it?)

We ask this question too, in our own way, within the lines of our own lives:

Why did God create us to need sun and warmth, and then send most of us into winter half the year?

Why was I given a child, whom I have always loved, who yet does not love me?

How can God give me such a passion for music---with no money for lessons or help?

Why did God plant the longing for eternity in bodies that will soon wither and die?

The questions blind us. I can't figure them out. But Milton’s poem ends, as all sonnets must. And it ends with this resolution. Though God does not need our labor at all, still, "thousands at his bidding, speed and post o'er land and ocean without rest" to do His will. But there are others of us who cannot move or even see. What of us? "They also serve who only stand and wait."

We are all of us blind in some way. Yet we are not done. God sees us stumbling, He sees us waiting in the dark. We can serve Him by simply waiting in the dark. And yet---listen! Here is the great irony of the poem.

Milton has done far more than simply "stand and wait." Even in his blindness, he has written a breath-stealing sonnet. A sonnet, mind you! The most rigid poetic form possible. And a sonnet that is considered one of the finest poems ever written.

What does this have to do with you and me? Even in your present darkness, you are still standing. And, likely, you are still serving. Still picking up kids, still fixing dinner, still balancing a budget, still looking for God in the calm and in the riot. (And maybe trying a cricket or a worm here and there.) There's enough light, still, in the midst of the questions to do good work.

I’ve seen some of your labor: the writing, the platters of lemon bars, the children, the photographs, the poems, the dresses, the prayers . . . And we do this half-blind!

There is yet enough light to serve Him.

Don’t stop.

And listen---more light is coming.

Very Soon.